Fener Nights

On my first morning in Fener, I was awoken by the pecking of a crow on the adjacent rooftop. At first, I wasn’t sure where I was.

The bed—with its warmth and softness—swallowed me up whole, like the arms of a lover. It was difficult to get up, and as I stared up at the wooden ceiling, I realized just how tired I was from the years I had spent trying to please someone who was impossible to please.

For the first time in a long time, I was alone. It was quiet. I could breathe and move at my own pace, without having to navigate the invisible currents of someone else’s volatile undertow.

It was 2017. My life was in ruins. A few months before this moment, I had finally found the courage to leave my abusive ex for good—at Shadwell Station in London. I could barely walk. He had beaten me so badly that managing the pain was all I could think about. As the train pulled away, I watched him grow smaller and smaller until he disappeared. My whole life had become entangled with his, so leaving him meant leaving everything behind.

When the pain subsided into emptiness, I realized just how messy the situation was. All his gaslighting had replaced my thoughts and feelings with his. I wasn’t sure how I felt, who I was, or what I wanted. But I knew that if I wanted to move forward and heal, I needed to return to where it all started.

A couple months later, by chance, I was offered a teaching position at a university in Istanbul. I accepted it, knowing it was the only way I could go back and begin my journey forward.

For the first few weeks, I stayed with a friend in Osmanbey while I searched for a place of my own. It felt good to be back in the city—and to experience it free from his constant control and jealousy. The city was no longer cut up into places I could and could not go.

At the university, I befriended a colleague. We clicked instantly. She was Kyrgyz, married to a Turk. As I asked her about life in Kyrgyzstan and Kyrgyz culture, she told me about her father, who was a shaman and a poet. I wondered if he was the one who had given her her name: Altynai, meaning “Golden Moon.”

It was Altynai who helped me find a place of my own. When I told her I was looking for a flat, she quickly called her previous landlord to see if he had anything available. And he did.

We agreed to meet at his office, just around the corner from the flat. He offered us tea and asked me questions about myself and my work. He then explained that each floor of the building had two flats, except for the top one, and that none of the flats had numbers—only symbols painted on their front doors. The one above mine was the Lighthouse Flat and home to a Turkish architect. The Syrian musician beneath me lived in the Seagull Flat. The one he was offering me was the Pomegranate Flat.

The flat was tiny but cozy, with a small alcove that looked out onto the cobbled street below. On the bed were decorative brocade pillows embroidered with Ottoman pomegranate motifs, and in front of the bed lay a multicolored kilim. Most importantly, the flat had a nice bathroom with a good shower, a comfy bed, and a sturdy lock on the front door.

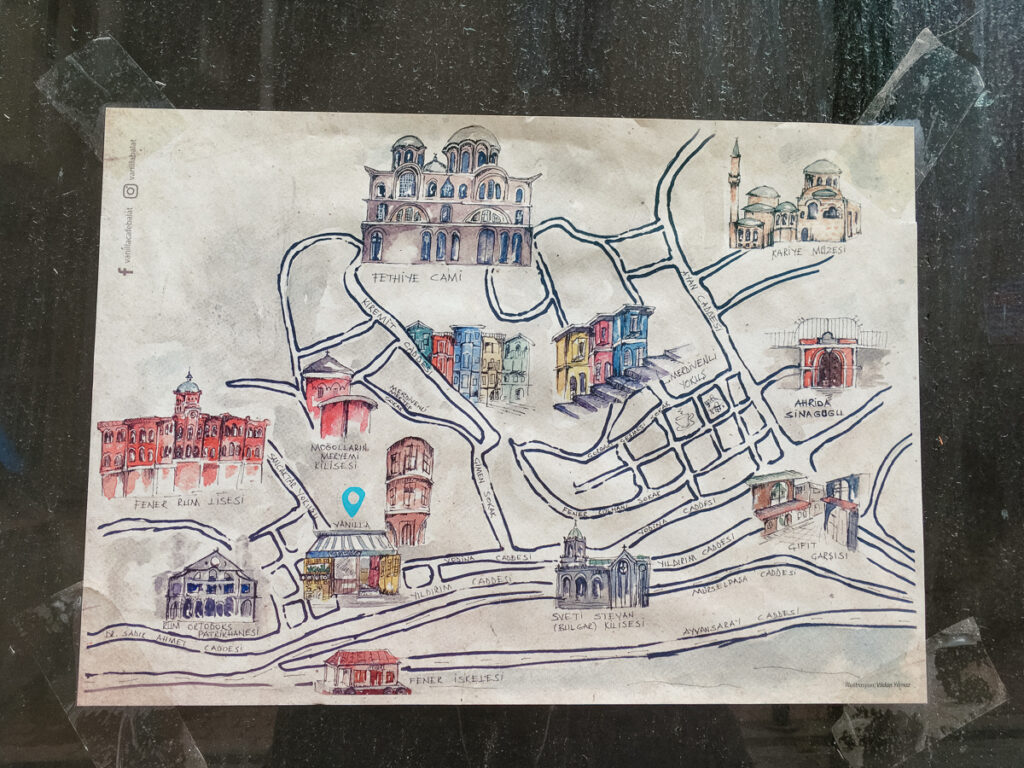

The next morning, as I wandered through the narrow streets of Fener trying to map the area around my new home, I discovered that this neighborhood was unlike any I had seen before.

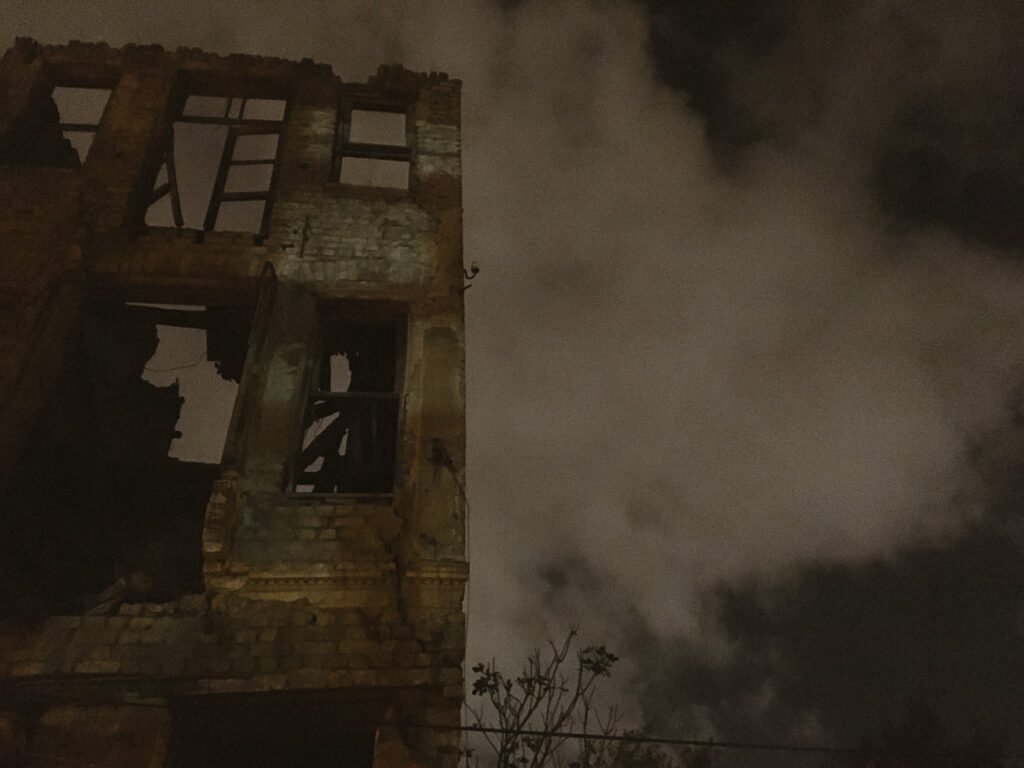

There were elegant stone houses, weathered wooden mansions, walled gardens, and Byzantine ruins in various states of renewal and decay. Many half-derelict houses lined the streets, in front of which children played—some barefoot, their laughter echoing off broken walls.

The whole area of Fener sits on a hillside that slopes unevenly down toward the Golden Horn. From higher points, there were views of the harbor and the city beyond.

The place felt liminal, caught between past and present, preservation and collapse—as if time had stopped, but not life. The streets were very much alive, filled with people going about their daily routines.

I later learned that the name Fener or Phanar comes from the Medieval Greek word phanarion, which means lantern or lighthouse. It originates from a Byzantine column in the area that had a lantern on top and functioned as a public beacon, possibly used to guide ships on the Golden Horn.

Since the 16th century, the neighborhood had been inhabited by the Phanariotes, who were under the protection of the Ottoman Empire and had gained wealth through commerce and trade. That wealth was funneled back into the neighborhood, where the Phanariotes built magnificent homes and palaces.

But with the rise of Turkish nationalism in the 20th century, the population exchange of 1923, the pogrom of 1955, and the expulsion of Greek citizens in 1964, the area lost much of its original inhabitants—and with them, its wealth. They were replaced by migrants from the Black Sea region, arriving in Istanbul in search of work and better living conditions. A lot of them settled into the abandoned homes in Fener but couldn’t afford their upkeep. They tried to adapt the houses as best they could, but many fell into disrepair.

As Autumn slipped into Winter, my life settled into a quiet rhythm of work and writing. Each weekday morning, I woke around 5 a.m., and while it was still dark, I made myself a cup of coffee and sat in my tiny alcove. I would prop the window open, still half asleep, and write in my journal. A little while after, like a spark caught by a wild breeze, the call to prayer would begin. First came the distant, echoing voices of muezzins ricocheting across the whole of Istanbul. Then our muezzin joined in, his voice steadier, more reserved, moving at a slow, hypnotic pace.

These were the days I woke in the dark, left for work in the dark, and returned home in the dark. The bus would pick me up and drop me off along the offshore highway. On my way home, once I’d braved the four-lane crossing with a traffic light no one waited for, I turned the corner onto Yıldırım Caddesi—and the noise of the world faded away.

Here and there, I would pass someone on the street on my way home but for the most part, at night the neighborhood felt deserted. Very few street lights lit my way but not once was I afraid.

What I felt instead was the absence of truly feeling anything at all. The trauma I had experienced in that emotionally abusive relationship had left a deep emptiness inside me—one I was in no hurry to fill. The absence of feeling was comforting. The absence of him was comforting.

For a long time, living in Fener, I felt akin to the ruins all around me—tall and determined to stand in the darkness without answers.

On weekends, when the weather was warm and sunny, Fener was overrun by tourists eager to hang out at newly opened cafés and take selfies against the colorful historic buildings made famous by local TV shows and Instagram.

To escape the crowds, I used those moments to venture further into unknown territory—but not alone. I had made a friend. A tall, handsome, metal-music-loving man from Damascus who was willing to wander with me. He was a colleague and my de facto chaperone, as I pulled him into places I was told no woman should go alone. Together, we explored the Theodosian Walls, the side streets of Balat and Eminönü, and when we were hungry, we headed to the Arabic market in Fatih.

But at night, my mind returned to the ruins.

Often, as I walked the streets alone, I would find children playing among the ruins—reinventing the spaces as fortresses, houses, or whatever their imagination conjured. From them, I learned that ruins offer a space for the observer to interpret freely, to fill the gaps with personal meaning and imagination, allowing what’s broken to be repurposed. And so, I began to reimagine the ruins of my own life.

But ruins are harder for adults. They force us to confront realities we often avoid. Like bones, they remind us of our own transience and the ways we’ve fallen short. They ask questions that are difficult to answer within the stories we tell ourselves about our lives.

What the Fener nights taught me was that healing isn’t always about immediate action or rebuilding. Sometimes, the most important part of recovery is pausing—being present with your pain, grief, or emptiness long enough to recognize what survived it. Returning to Istanbul allowed me to reclaim parts of myself I had given up in my abusive relationship and while doing so I was able to reclaim my relationship with the city. It was no longer just the place where it all started – it was also the place in which I discovered who I was when everything around me falls apart.

After the collapse of a relationship or identity, we often rush to redefine ourselves, but there is value in simply being with what’s left—your instincts, your resilience, your sense of self—before deciding what comes next.

x Martina